In

northern

England, the

wee corner of the world I call home (actually, I often call it hyam,

but that’s a whole other discussion) we have a phrase, “there’s

nowt so

queer as folk”, meaning that there’s nothing quite so odd,

eccentric, strange, unusual, unique, funny as people are. I was

yacking

away

a

few days back

with a dear friend and serial brain-lightbulb catalyst of mine and I

used the word queer in this sense. She said that young people around

here (‘here’

being the eastern seaboard of the USA) don’t use the word that

way any more, and that got me to thinking (always a dangerous thing to

do).

|

| The 1999 British TV series Queer As Folk did much to challenge taboos about homosexuality in the UK |

The

word ‘queer’, in its ‘unusual’ sense, first turns up in

writing in 14th century Scots, possibly from Low German

and related to the word ‘quer’, which my German-English

dictionary tells me now means ‘transversely’ (Lesbian, Gay,

Bisexual, Transverse anyone?).

By

at least the 19th century it had gained certain pejorative

senses, such as ‘unwell’ or ‘in financial difficulty’. In

the 1904 Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Second Stain”

(Twice in one night! Good work, old boy!), Inspector LeStrade

threatens an unruly police constable with dismissal by saying they

would “find [themselves] in Queer Street” (using the modern sense

of the term, that sounds like rather an enjoyable Friday night).

|

| The Marquess of Queensberry - as charming as he was well-lettered. |

One

of the earliest references to “queer” in its meaning of same-sex

attraction, was in an 1896 letter by John

Sholto Douglas, the

9th

Marquess of Queensberry,

famous for publicly

endorsing the ‘Queensbury Rules’ that form the basis of modern

boxing and for bringing about the arrest of Oscar Wilde for “posing

as a somdomite” (clearly spelling was not Queensberry’s strong

suit) by

living

as a couple with Queensberry’s son Lord Alfred ”Bosie” Douglas.

|

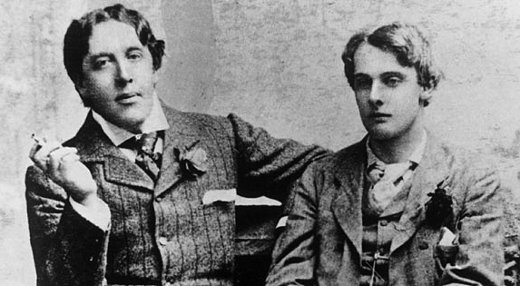

| Oscar and Bosie |

The

letter referred to “snob queers like Rosebery”, speaking of the

splendidly monikered Archibald Primrose, 5th

Earl of Rosebery, who Queensberry

suspected

of being one of his son’s lovers.

|

| Archibald Primrose |

Throughout

the 20th

century, the term queer was used either euphemistically or abusively

to

refer to homosexual men. It was in the late 1980s that the process

of reclaiming the word began. “We’re here, we’re queer, we

will not live in fear” came to be a popular chant at gay rights

rallies.

A

pamphlet passed out at 1990’s NYC Gay Pride by the

organization

Queer

Nation explained

the reasons for taking up the term:

“Ah,

do we really have to use that word? It's trouble. Every gay person

has his or her own take on it. For some it means strange and

eccentric and kind of mysterious [...] And for others "queer"

conjures up those awful memories of adolescent suffering [...] Well,

yes, "gay" is great. It has its place. But when a lot of

lesbians and gay men wake up in the morning we feel angry and

disgusted, not gay. So we've chosen to call ourselves queer. Using

"queer" is a way of reminding us how we are perceived by

the rest of the world.”

And

it is true that to be queer is to be unusual, to

be abnormal. Less than

2% of the population in the UK and USA identify themselves as bi- or

homosexual (although

the percentage of those who’ve had some sort of same-sex dalliance,

tasted the cherry chapstick if you will, is almost certainly

considerably higher).

It’s also true that being left handed (around

10% of the population) is

queer (in its “nowt as queer as folk” sense),

as is having red hair (less than 2% of the world’s population) or

being black in the UK (3%) or Caucasian

in China (a small enough percentage to be classed as a trace

element). And

all of these minorities have suffered, or still suffer, various forms

of prejudice and discrimination.

But

normal, like natural, is a term that is often dusted with a patina of

positive connotation that it doesn’t warrant. Strychnine and arsenic are both natural, but I wouldn’t be overly inclined to

sprinkle a little on my organic, quinoa salad. In

a similar way, for the vast majority of history (and most probably

its illiterate older brother prehistory) slavery was normal, but that

doesn’t incline me to propose it as a handy solution to the irksome

problem of having to do tiresome domestic chores.

|

| John Stuart Mill |

Indeed

I would contend that the increased tolerance of queerness, of not

being the norm, is one of the greatest achievements of the

enlightenment. The

philosopher John Stuart Mill’s corrective against the danger of the

tyranny of the majority inherent in the utilitarian ideal of

achieving “the greatest happiness for the greatest number”,

enshrining that an individual should be free to do whatsoever they

choose as long as it does not harm others, is a vitally important

underpinning of modern democracy.

“The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinion of others, to do so would be wise, or even right...The only part of the conduct of anyone, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns him, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign”

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859)

At a time when acceptance of homosexuality is thankfully on the rise in many parts (though by no means all, I’m looking at you Uganda) of the world, but tolerance of other forms of diversity of action and opinion is in great danger of being clamped down on, I would make the modest proposal that embracing queerness, in all of its senses, is something we would do well to encourage.